A dialogue on art, philosophy and self irony

Jan. 16, 2022

8 Concepts From Julijonas Urbonas, A Father Of Gravitational Aesthetics

The artist’s designs and the philosophical optics

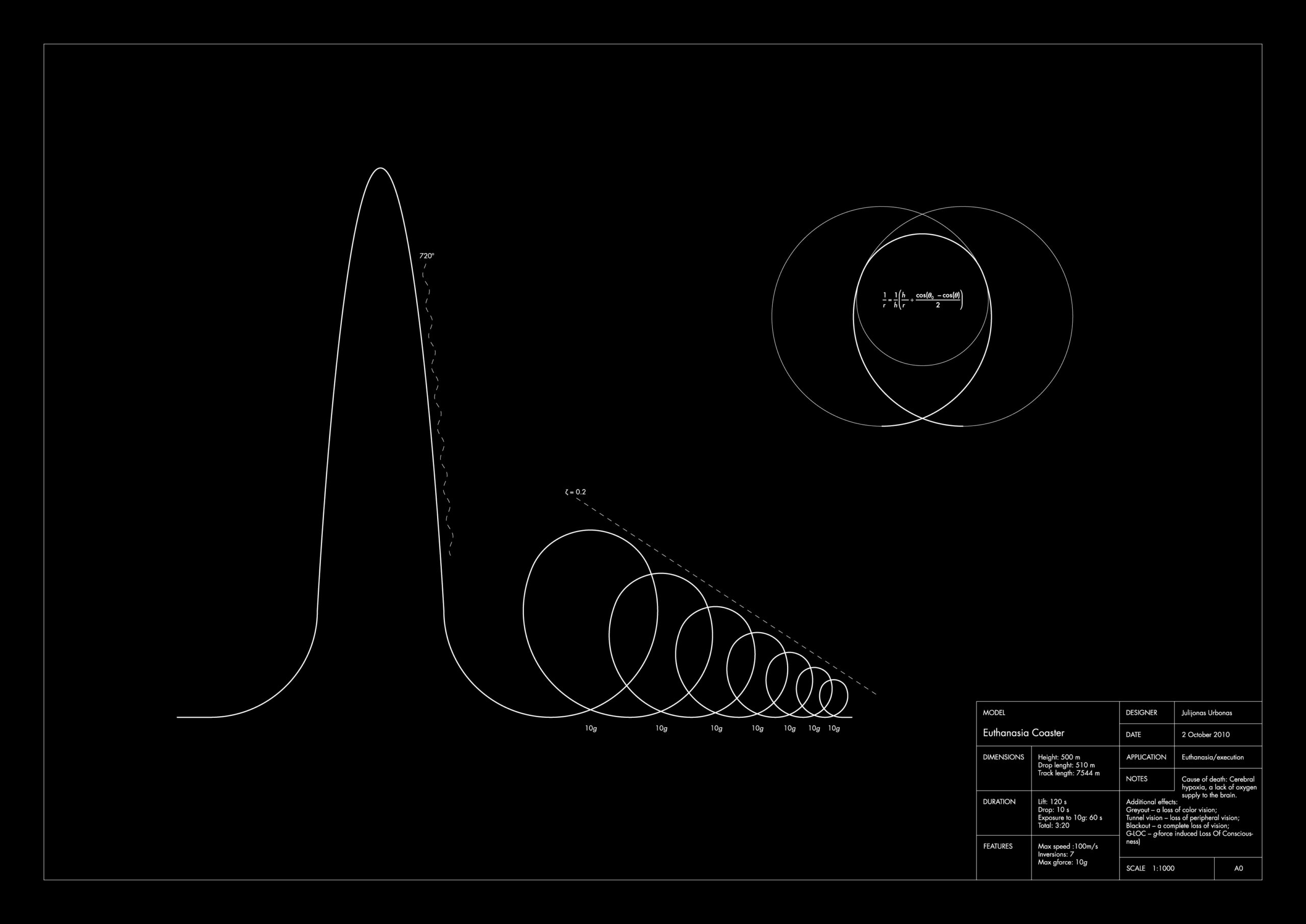

It is not easy to introduce Julijonas Urbonas. His intriguing and somewhat controversial projects include an euthanasia roller coaster designed to put a rider into a euphoric state before killing them, the “cumspin”, which uses gravity to enhance the orgasm of the user, and a planet of people, which is essentially an artificial planet made of human bodies stuck together in outer space.

Immerse yourself in the eight random artistic concepts that came up during the conversation of Urbonas and Lunatum Mag about the artist’s designs, gravitational aesthetics as well as the philosophical optics.

There are many sides from which you can look at this man from Vilnius: an engineer, a designer, a modern artist, an inventor. Some people would possibly call him a mad scientist, some would admire the way he mixes performance and genuinely innovative ideas, some would enjoy the laid-back manner in which he describes the most sophisticated ideas.

“I won’t go too deep”,

he promises and then for ten minutes he deconstructs a concept or two.

“It’s quite a long story, how can I make it short…”,

he says and then we talk about it for fifteen more minutes.

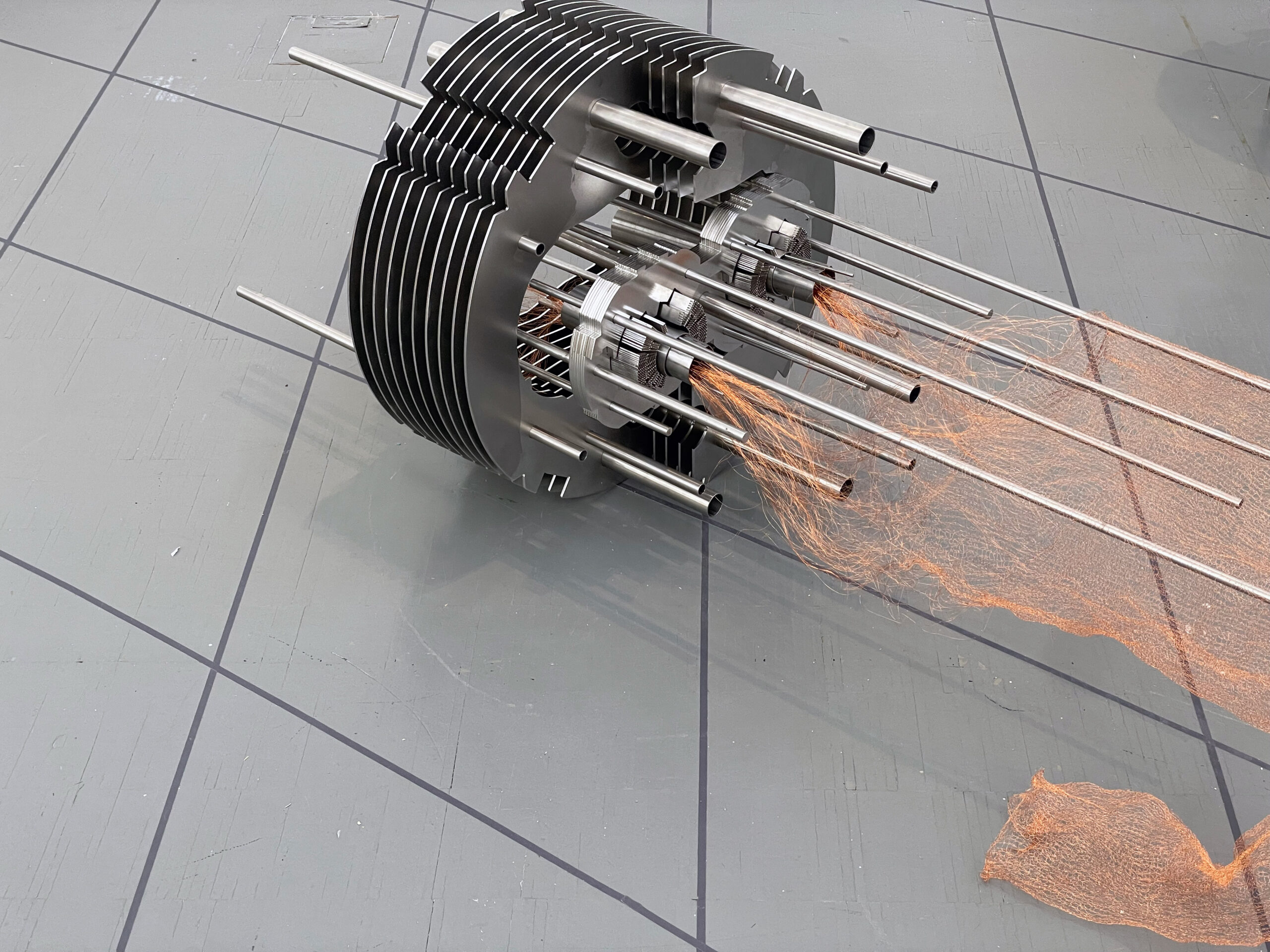

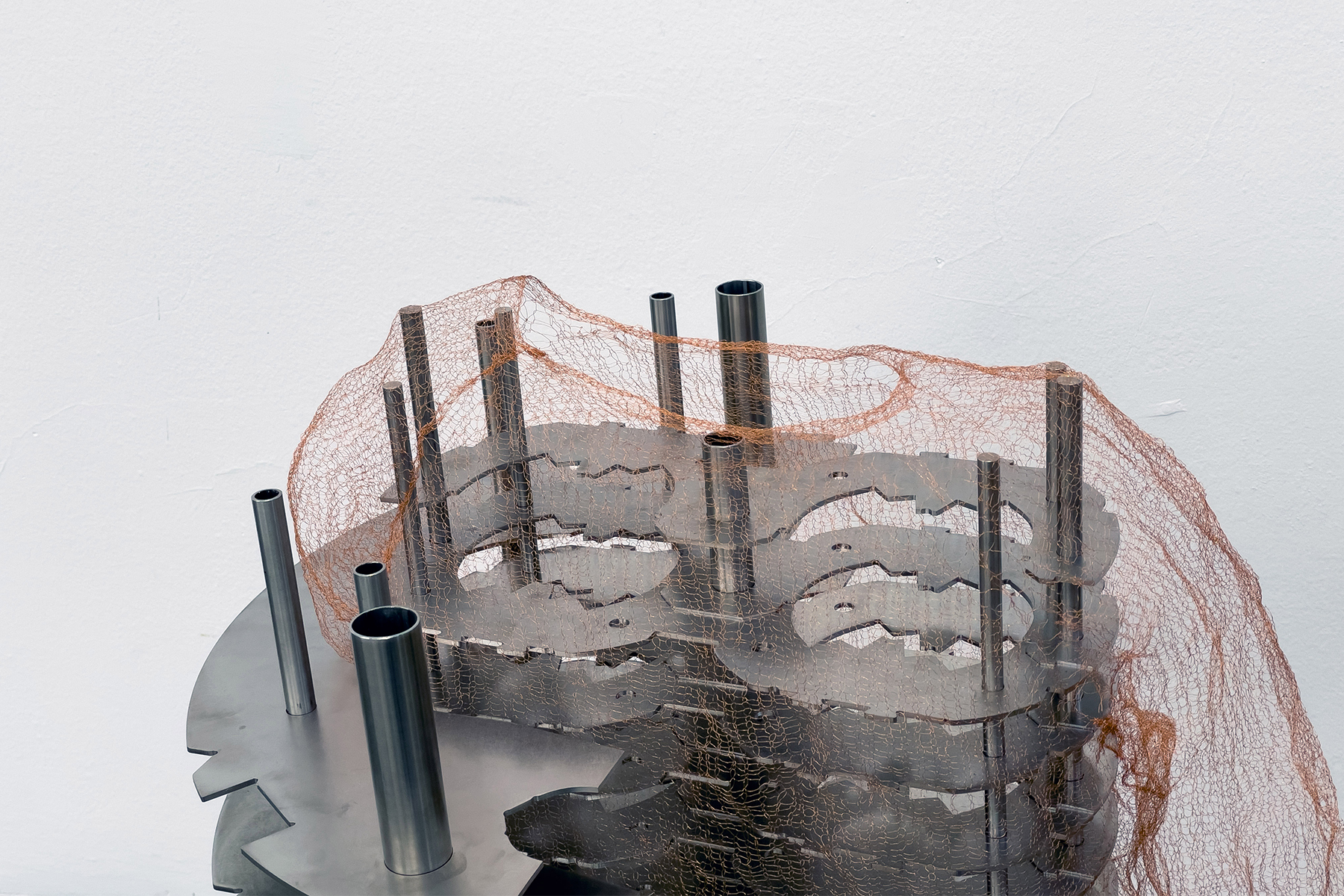

At the Milano Triennale 2022, Urbonas presented his latest project called "When Accelerators Turn into Sweaters". This is a full-scale replica of one of the Large Hadron Collider parts that weaves superconducting fibers into sweater-like knit-work. It is not for commercial purposes, of course, as the thing can’t make actual sweaters. Currently, he is working on some amusement park rides, one of which is planned to be presented next year.

What is this choreography of human bodies as the core principle of his work? We explore it in this interview, diving into Urbonas’s views on life, death, body, religion and home.

Interview

by Boris Starodubtsev

How would you describe yourself to someone who doesn’t know you? What is your most essential feature?

There is no such thing as essential in my practice. It all depends on the context. When I want to introduce myself, the very first thing I do is look in the eyes of a person and try to feel how they would label me. People still have a certain impression of you whether you want it or not. They judge by the way you behave, the way you communicate, the way you look, and sometimes use a certain label. So, I look in the eyes, see that this person is going to label me as an artist, and then I jump and say: ‘No, I am an engineer’. I would go in the opposite direction in order to confuse, but also to provoke a discussion. That’s why I wouldn’t label myself in a particular way. I’m in between those disciplines.

How many of them are there actually?

Well… let’s count. Artist, researcher, engineer, designer, writer, lecturer, director of both commercial entities as well as director of theater opera and so on.

You were also a director of an amusement park.

Yes, and I’m still a director of a company that, well, is not producing yet, but working on the prototypes of future amusement rides. It’s very complicated. I have been working already for fifteen years on some amusement rides, and still we are in the state of prototyping. It’s really difficult to move bodies in space. I mean, in some way it’s easy, but what is difficult is to make it public. You have to go through all kinds of institutions to get certificates and so on. Lots of testing.

Do you have a release date for some prototypes? Maybe in a year, or in five years, or in ten?

(laughs) It’s being postponed all the time, but probably there is one that will be presented by the end of next year in Italy! It’s gonna be a robotic motion platform. In technical terms, it is called a stewart platform or parallel robot, which is usually used for flight simulators or vehicular simulators. But instead of recreating the experiences of a driver or an airplane pilot, we are going to use it with dancers. It’s going to be a little bit like 4D cinema, but in this case it’s going to be a 4D dance performance.

You will have a dancer — a real dancer and the machine. There would be a queue of people, one person will be fastened to the machine for two minutes, the machine would move and produce all kind of experiences, from thrill rides to acrobatics, and at the same time, the dancer will dance around so it will be an interaction between what is going on in the dance and in the machine. An amusement ride merged with choreography.

I hope I will get a chance to ride this one.

Concept 1. Human bodies choreography

You design and build very elaborate mechanisms based on very peculiar/bizarre ideas. Where do you get these ideas? What must happen for an idea to become a project you spend a couple years on or even more?

This might look very complicated. Sometimes ideas take two or three years to become a visible material. Sometimes it is very expensive, but in the beginning it is very simple. I always start with a dance, a choreography. All my practice is based on a certain kind of choreography. I think of human bodies moving in space and of a specific way they would move that has never happened before. It has never been even imagined.

Take the Euthanasia Coaster. In the core of the project is basically the falling machine that I designed. I thought of this particular motion in space without looking into technology. How can I think of such a movement that has not been even imagined? What would it take to make it as real as possible? There are quite a few ways to think of such motion or such choreography, but my style is extreme. I look into specific kinds of extreme choreography that would push the human body and imagination to the extremes, so that it would almost look like it’s impossible to go further. That’s why some of my projects are quite controversial, but it's more like a side effect.

And when we speak about the core of my extreme choreography, think of having a group of people catapulted into nothingness. How would you define nothingness? In the public imagination, it is usually something like whiteness or blackness, but whiteness and blackness are already environments. Real nothingness is something really difficult to imagine!

Two or three years ago when I was into space arts, I came across this unique kind of cosmological phenomenon called Lagrange points, which I consider the most accessible equivalent of nothingness. It is a super cold, dark, vacuum and most importantly weightless. There are always five Lagrange points between two celestial bodies that are orbiting around each other. Two gravities of the celestial bodies attract each other, and at these points they cancel out each other. Imagine you find yourself at one of the Lagrange points with a bunch of other people, like three million or trillion people, and at that moment the most beautiful extraterrestrial dance would happen. The frozen bodies would float freely there until they would start falling into each other and converge into a blob due to their own weak gravities. In this way, a new ‘human’ planet would be terraformed.

This thought experiment turned into the large-scale artistic and scientific feasibility study ‘Planet of People' that was presented at the Venice Biennale last year. It was a very complex and complicated project, but originally I was thinking just about a simple thing — a group of people finding themselves in the absence of an environment, a sort of humans-without-world situation.

It is really interesting in the way that you have to forget what it’s like to be a human.

Humans are terrestrial beings. We are as we are because of the Earth ecosystem. Gravity, for example, has been the great designer because, if you think about it, all our features are the result of negotiation with gravity.

And if there is no gravity, there is great confusion, both physical and intellectual. You have to forget everything that you define as terrestrial or human — culture, nature, race, politics, everything that might be seen as terrestrial. In this case, it is interesting to think of a human being as something totally different, a sort of human alien.

Concept 2. Life on Earth

Correct me if I’m wrong. When you are catapulted into the cosmos, you are dead.

When it comes to the definition of life and death, you have to radically rethink. When we define life on Earth, even the most conventional biologists can not agree upon the specific definition of what is a living being.

Actually, I planned to ask how you would define life on Earth.

Life can be defined in quite a multitude of ways. I’ll give you an example.

There was a 20th-century desert explorer, geologist, Ralph Bagnold, who spent almost all his life studying sand dunes. Having spent forty years trying to define, through all kinds of disciplines, from material science to cybernetics, what a sand dune is, he defined it as a living being. ‘Nonsense’, someone would say, but his research has contributed to the emergence of astrobiology and what I’m trying to say with this example is that there are quite a few ways of looking at what we think is well known to us.

You could actually see certain new models of living beings, of living structures. If you go to more extreme fields of astrobiology, you could say that extraterrestrial life is something that is impossible to know and to get access to, because it might have a lifespan of trillions of years or the size of lightyears, and we don’t have imagination of such scales and tools to deal with it. So in my case, I’m more into provoking questions rather than answering them because I don't know what it will lead to.

So the Planet of People actually has something to do with life on that planet, right?

It’s almost like an extraterrestrial cemetery for and of human beings. Lots of people consider it as an apocalyptic scenario. Maybe instead of thinking about how we should survive, we should think about how to monumentalize ourselves for eternity over there.

We could think that it’s just about death and nothing else, but actually it's a lot about life because, through these provocative projects, you start to think about life and about the fragility of yourself.

Concept 3. Home, Body, Technology

It’s interesting how you question the conventional definitions of concepts. I’ve got one more for you. You see, we want to build Lunatum Mag around certain topics. The first issue is about home in the broadest sense. Do you have a place you call home? What is home for you?

Well, there are quite a few ways to look into that. That can be something very pragmatic and everyday, mundane like. I spend lots of time in a very specific environment which might be just my studio. Here I’m on the second level of my studio, and I built it in such a way that my personal life would merge with my studio work life.

On the ground floor, I’ve got my dirt life: kitchen, toilet and studio, and everything is on wheels, so I can move around, reorganize my life. On the second floor, I’ve got my clean life. Clean Life — I mean bedroom, guestroom, as well as computers, my academic life and so on. But now I realize that it is not possible to separate these different kinds of lifestyles. Sometimes I wake up with hydraulic oil in my armpits (laughs), or metal pieces in my ear.

But If you think of home as a concept that could be questioned, it’s really something like a ghost. You can say that home is something you can define, but at the same time you can’t. You can see through it, but you can’t grasp it.

My home is something that I question all the time.

Like in the Planet of People project — what did I do in this case? You could say that I reduced the definition of the home of mankind to human bodies.

As an Italian philosopher Emanuele Coccia said, the human body is like a walking zoo. We are partly bacterial, we are partly fungi, partly other microbiome, also ninety percent of us are other beings — plants and animals. Besides, we are also technological beings. We have been technologizing ourselves in such a way that the term cyborg doesn’t make sense, because we are already cyborgs. The very structure of our muscles and bones are already technological inventions that emerged in specific evolutionary moments of human history.

Our bodies are a very complex home, super complicated both materially and conceptually. I’m rethinking it through my projects and encouraging others. It’s also impossible to separate ourselves from the environment, and this is where it brings me to the concept of ecology because ecology is always about interrelatedness. You can not talk about a specific biological entity without touching upon some other living being. Ecology is home on a larger scale.

When you start to define something, you always have to pick a specific kind of ideology, and this is also very complicated, because today we are encouraged to think in the plural. We increasingly no longer believe in one particular thing. That’s why everything now is becoming quite speculative and I would say quasi-fictional,and you start to believe in several such fictional truths at the same time, being aware that it may turn false or different anytime soon.

And that is why everything we have been talking about here, everything we’ve been defining could be considered a kind of fiction. We’re becoming more and more aware that everything we believe in, all the labels we use, whatever you pick, everything is imaginary. That is something that has been popularized by historians like Yuval Noah Harari (an Israeli historian and the author of the popular science bestseller ‘Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind’ — Lunatum Mag). It defines this moment in human history when we got the ability to think of something that does not exist such as monsters, gods, religion, economy, everything that today is often, if not always, taken for granted or even considered as a fact and truth.

Once you realize that everything is fiction and imaginary, how do you behave? How do you even just live on? In my case, I think that this current inclination to think speculative, to think about several alternatives of reality, several coexisting ideas at the same time is something that allows us to navigate between those different kinds of possibilities of defining home, both on a personal level and much larger ecological or cosmological level, and my practice is about that.

I think I was explaining too much! (laughs)

It was a beautiful journey through concepts.

Concept 4. Future of the humanity

Are you worried about the future of this planet? How do you think this planet will stop to exist?

The more I am into my fatherhood, the more I am becoming worried about the planet’s future, but still retaining some optimism. I read an article somewhere about a scholar who had spent a few decades researching the history of apocalyptic scenarios and noticed that once we predict something bad is coming we start to prepare and develop solutions, and that is one of the reasons the most probable scenarios do not come true.

I believe in science, which has to offer quite a few apocalyptic scenarios, but at the same time I am aware of its weakness when it comes to predicting the future. For example, there is no logical contradiction in imagining a future in which the laws of science/physics/nature would no longer hold, thus implying the possibility of the end that is impossible to predict.

This insight is related to the 'black swan’ theory that says that such events can happen unexpectedly and suddenly (the theory was developed by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, a Lebanese-American writer, trader, risk analyst). That is why I believe to have to be prepared even for such a scenario that humanity would end at an instant. In this worst-case scenario, if we have to come to terms with the end of our planet and history, I am concerned. What human legacy, apart from space debris, will we leave in the Universe? One could consider analogues of the golden phonograph record, on which images and sounds of Earth's life and culture are recorded, sent in the space probe Voyager. However, nothing can be a substitute for a human being. The idea of an artificial planet made up of human bodies might be an appropriate proposal of such a monument for humanity out of humanity.

What will come after humanity? Will there be any rules and laws?

There are already quite a few scientific and fictional speculations about such a future. For example, Dougal Dixon's ‘After man’ or Jan Zalasiewicz’s ‘The Earth After Us’.

In the aforementioned project ‘Planet of People’, I imagine a radically different kind of life after humanity. You may think of human ‘bricks’ that form the planet as quasi-living beings, a sort of cyborgs. Actually, the term ‘cyborg’ was originally coined to define a modified human who could survive the hostile environment of outer space, but what would a population of such cyborgs suspended in the nothingness of the cosmos do? What would their lives look like? If there is no longer need for breathing, eating, sleeping, or defecating, would such phenomena as culture, art, architecture, or love exist?

Concept 5. Freedom of limits

Back to your projects. They seem to question the limits of this reality. Do you feel uncomfortable in the limits that this world has?

No no no! I’m very aware of our limits. Those limits are quite simple. You see (shows me through the camera) — this is how far my hand can reach. I’m always aware that there is something that is impossible to have an access to, but anything, even mundane things like a pencil, has something that we don’t know about them. Whatever you pick, there is always some kind of a limit, but there is also something unknown, and being aware of this opens up lots of possibilities for me to interpret things. A good example is when the object starts to break it shows itself in unexpected ways. Or, as you can see in my practice, we can bring things to absurdity. Because I think everything is possible in a way, even those things that might seem impossible in the terms of science all of a sudden might behave in a way that is not scientifically understood. You could think of anything becoming anything. That's something that allows me to be free of my limits. At least at my daydreaming time! (laughs)

It's rather encouraging, you know. You are aware of your limits but your imagination lets you interpret things and concepts the way you want.

Imagination requires training, just like your physical body. It requires a substantial amount of time and energy spent on imagining things. If you don’t do this, you become limited all of a sudden.

Concept 6. Amusement Rides

Did your childhood in Klaipėda influence you to become who you are now?

Of course. My whole practice is based on my insights that emerged in the amusement park that my father headed. There were moments when I realized that I would have a very specific, very unique kind of knowledge of making people motion sick. You know, the amusement rides are built for making people sick and enjoy it.

But the interesting thing in my childhood was that I actually didn't like to ride the rides for several reasons. One of them was that the Soviet amusement rides for me were too boring. Another is that I easily got sick when I rode them. So, I was in a paradoxical situation of living in a park where you actually don’t ride, but at the same time knowing how it works. Being very close and in a critical distance at the same time.

That situation encouraged me to philosophize.

Why do so many people queue up, sometimes for two hours — for two hours! — for one amusement ride to have one minute of torture, you know, of sweating, shouting and vomiting, and the next day they came back to get more.

Even when I was a teenager, I was already looking into all kinds of theories from psychology to philosophy. And when I took over the position of my father and I started to run the park, I was already doing some experiments. For example, I was slowing down the machinery, or adding some effects, even sometimes commissioning soundtracks composed by well known composers or DJs for amusement rides. I realized that amusement park rides have a very unique aesthetic potential that has not been developed properly, because it has been driven by macho power. 95% of amusement ride engineers and designers are male, that's why the vast majority of amusement rides are about getting taller, faster, more intense.

And I thought, well, what an interesting phenomenon. Think of any artistic medium or genre, or even not just art, anything. Would you find something similar where the bodies would be moved in space in different ways, and that motion of the bodies would be considered as something pleasant or appreciated aesthetically?

In an academic circle, it is called egomotion, aka self-motion experience. It’s not choreography or dance. It's more like a vehicular experience, and I thought that it was something that had not been developed in the arts, and invented the term gravitational aesthetics. This is something that you experience while being moved in space, and this insight has been driving my whole artistic career.

Later, I started to develop creative strategies and sub-genres of gravitational aesthetics, such as vehicular poetics and design choreography.

For example, vehicular poetics focuses on the aesthetic, imaginary and evocative qualities of travel. Yet, by its function, the design object here is a vehicle, a technical means used to transport people, but also, and more importantly, a narrative vehicle carrying its passenger to the aesthetic realms of poeticised travel, be it physical or imaginary. Here, the way the bodies are moved could be seen as storytelling. For example, think of a car as a 360-degree cinematic machine of a road movie. As another example, a roller coaster is perhaps one of the best examples of such storytelling. It is basically a falling vehicle, of which the falling trajectory, the track, could be interpreted as a sort of gravitational storyline. The gravity-assist vehicle is capable of manipulating both horizontal and vertical dimensions, and mobilizes its passenger to a unique whole-body engaging aesthetic domain full of unique experiences found in car racing, acrobatics, dance, etc., and rarely if not found in other forms of narratives.

So, I was developing this specific kind of genre, and other genres of gravitation aesthetics, and all the previous projects that I mentioned belong to the same kind of gravitation aesthetics.

Concept 7. Threads of the Universe

Your latest project, ‘When Accelerators Turn into Sweaters’ is a good example of how the inventive mind comes up with the most unusual ideas. How did you decide to mix the most profound scientific experiment with such a cozy idea of knitting sweaters?

One of the ideas that was driving me in this project was basically the search for levitating technologies. And actually, while spending some time at CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research, the site of the Large Hadron Collider, and the world's largest and highest-energy particle collider — Lunatum Mag), I came across superconductive materials that actually make particle physics possible. Particle accelerators are made of superconducting materials.

I am not going too deep into the technical terms. What is interesting about this superconductive material — once it’s frozen, it is levitating in electromagnetic waves.

It’s called the Meissner effect. These materials are sometimes used for making Maglev trains. You might have seen them in Japan, the trains levitating on the electromagnetic field.

To make these materials levitate, you need to cool it down to almost absolute zero with liquid nitrogen and liquid helium. I was wondering, what if this material was affordable and possible at room temperature? What effect would it have on art, design and architecture?

And so, I was wondering what kind of prototype I can make from this material to imagine this kind of alternative reality where this material is possible at room temperature. I conducted a lot of experiments and realized that the majority of these materials are actually threads. And one experiment was about knitting all kinds of stuff, from socks to abstract objects. Worth mentioning, it had to be done under water, because the material could be damaged or even ignite under exposure to oxygen.

I wanted to mix it with some mundane objects so that it would be easier to relate to, to empathize with them. Something that you can wear really worked for me because it’s easy to imagine what it would be like to have something like a levitating sweater. But there is something else in it, because, as I’ve already said, most projects are about many things at the same time.

Scientists at CERN, and also quite often physics in general, say that the core aim of their research is to look at the building blocks of the universe. But I found this metaphor somewhat untrue, as I did not see our universe made of blocks or bricks. For me it consisted of something rather more dynamic and fluid, like lines and threads. And this is where my criticism of the scientific language brought me to anthropologist Tim Ingold, who does an anthropology of lines, and he says that the universe is not made of blocks, but made of lines. He employs a line both as a metaphor and epistemological device to talk about almost everything from the definition of life, creativity to science and technologies.

This is where I started to look into why scientists use these specific metaphors like blocks of universe and how actual technology and tools they use affect their language, and thought: what if I make poetic abuse of their equipment to provoke different kinds of metaphors, to think of not blocks of universe but lines of universe. So, I took the core of the accelerator and dismantled it until I just got loose threads and I got an extreme knitting expert (extreme knitting — knitting done under difficult conditions; in this case under water and with hard and rigid threads) to knit a sweater from the threads.

There is not a chance to use it commercially, right? It cannot knit a real sweater.

Well, in order to make it functional, you need to, as I said, freeze it, and you will need huge, expensive and dangerous equipment. So every time I'm asked by museums and galleries to show a piece, I ask if they could afford the equipment to freeze the stuff. None of the museums could afford this.

Concept 8. (Un)real agency

You founded the Lithuanian Space Agency. Is this a real agency with employees and projects?

It is real, and it is not. (laughs) First of all, I founded it, I would say, as a bureaucratic or corporate set design to the ‘Planet of People’ project to make it sound more real.

Last year, I presented the project at the Venice Biennale, and I wanted to make it even more convincing like a real space agency working on it. And it was so successful, that once we started to write emails to well known scientists — astrophysics, astrobiologists, astropolitics, quite a lot of them paid attention and gave opinions, sometimes even looked into the feasibility of the ‘Planet of People’. After that, we even published a book — a collection of texts, images and calculations of scientists who looked into the possibility of making a planet of human bodies.

Of course, the majority of them knew that it was kind of a joke, but it's a joke based on science. A serious joke.

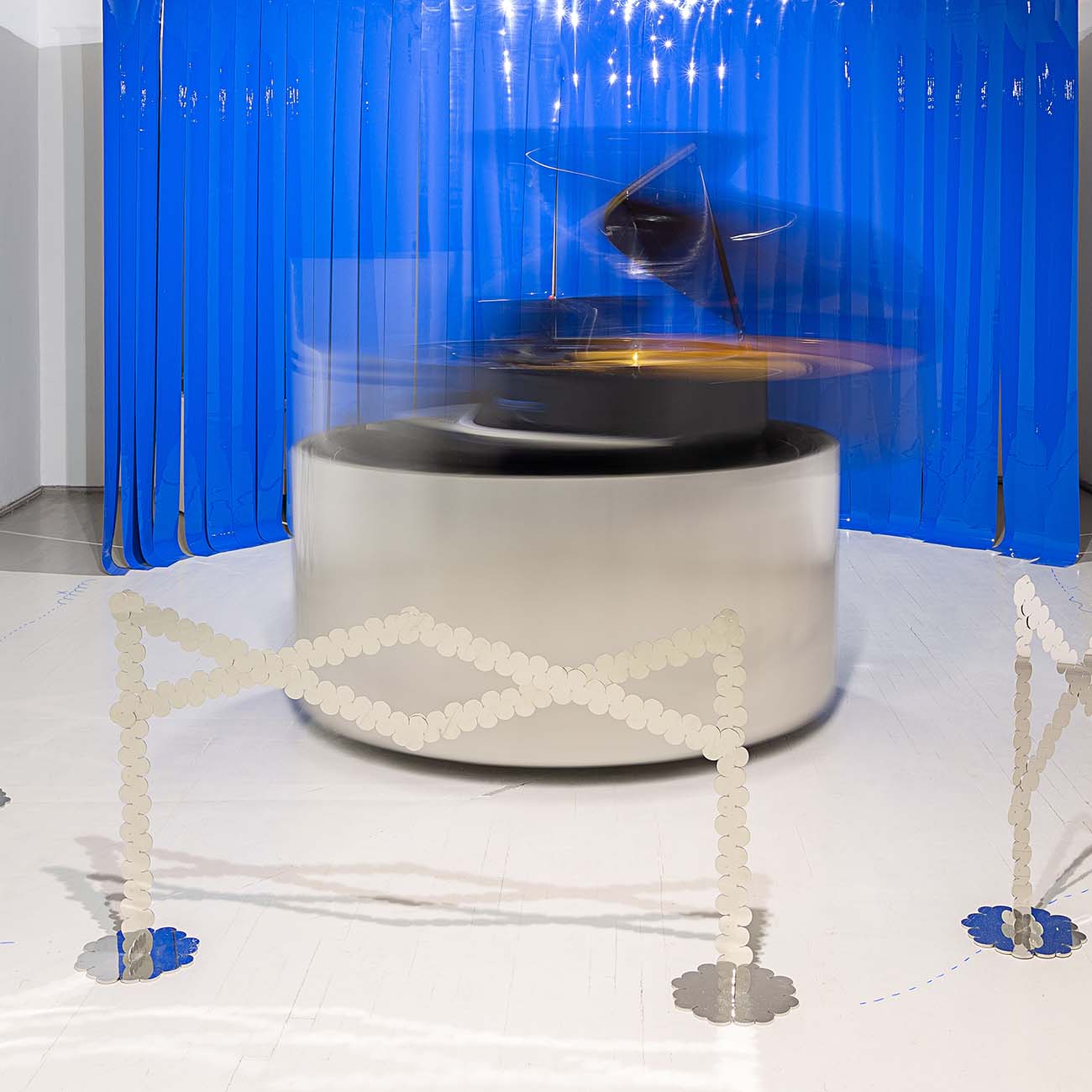

On the other hand, sometimes I think of this institution as my specific line of work based on a very simple objective: to look into art and culture that is exposed to altered states of gravity. I could say the activities of this institution is to put certain cultural activities under weightlessness, and one of the examples is my “Hyper-gravitational piano”. I matched a human centrifuge, which is used for astronaut training, with a grand piano. It was staged as a three-month performance-experiment or high-g sound training with weekly concerts of Gailė Griciūtė, a composer and piano player, in which we were increasing the speed of the platform and contemplating the effects of altered gravity on both the piano player and the composer, the instrument and the sound, the music and the listenership. I like to think that all of these unique physical and mental conditions gave birth to what can be called an extraterrestrial sound.

Are there people, artists, engineers, writers, philosophers whom you would call teachers or mentors?

Well, quite a few. I could say that I was quite affected by the fathers of critical design Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby. Actually, Anthony Dunne was my PhD supervisor while I was doing artistic research at the Royal College of Art. He was crucial for my artistic practice.

There are a bunch of different kinds of thinkers and artists who are affecting my thinking and making, from Paul Virilio, who was a philosopher, but as well an architect, to William Forsythe, a contemporary choreographer; from Tim Ingold, the anthropologist that I already mentioned when spoke about the anthropology of lines, to Peter Sloterdijk and Bruni Latour, the philosophers.

Mostly, I am influenced by people working on specific topics that correspond with my current interest. Now, if I'm interested in the extraterrestrial imagination, I would say: OK, I'm interested in a specific group of thinkers, for example, Lisa Messeri, an astro anthropologist. She's really inspiring for me, but once I would go into other topics, it's quite possible that other thinkers, artists, engineers, cinematographers would be inspiring for me.

It's fluid and it's changing.

Edited by Sima Piterskaia

See Julijonas Urbonas's website.

Selected Articles

Two ChairsProject type