A dialogue on art, philosophy and self irony

Mar. 6, 2023

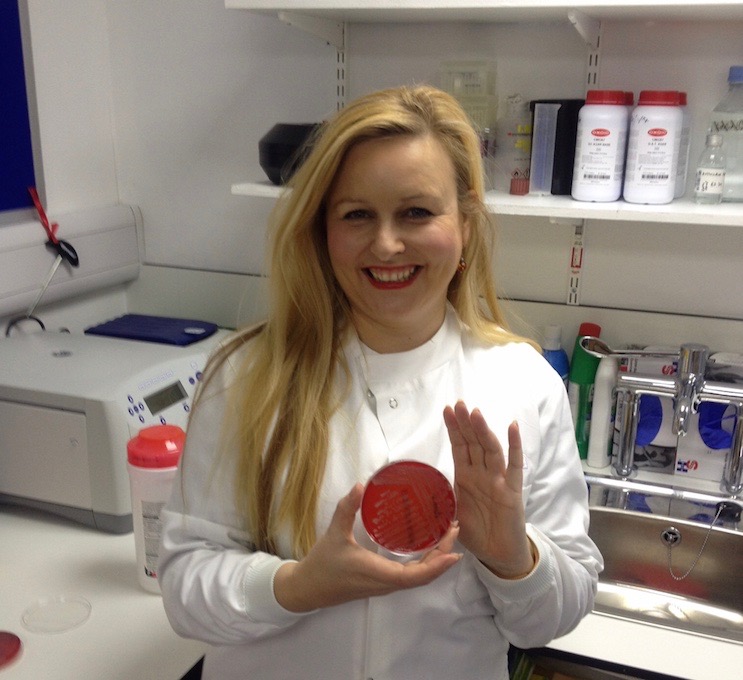

‘We wouldn't be here if it wasn't for bacteria’, Anna Dumitriu, the author of a Wearable Cure of Plague

When science meets art on the verge of fear

© annadumitriu.co.uk, Zenexton

Her art, or to be precise, bio-art, is poetry. She created an amulet that alchemist Paracelsus couldn’t. Tied with a robot, she caught that moment of consciousness emerging, and she deconstructed a dreamy, yet deadly image of plague, ripping the heart out of its core and using it as a weapon inside a delicate symbol. This is just an account of the story of a fantastic contemporary artist, Anna Dumitriu. Read the interview to learn more about the person behind it.

About ten years ago, I interviewed a scientist, a chemist, who was working on LED technologies, testing their features in a lab. Stuck in my own oblivion of bias about science, I asked her if she was happy about her choice of profession. “Why shouldn’t I?” she responded. “It is magic and rock-n-roll when merging these little things and then waiting for them to evolve into something completely new and unexpected.” This interaction was a pivotal moment for my perception of science, making me greedy for non-fiction and every little piece of art that works with gravity or energy. Then there’s also bio-art which is a whole different level of scientific comprehension, and when I ran into Anna Dumitriu’s works, they surprised my inexperienced mind.

Born in Brighton, she’s collaborated internationally and exhibited all around the world, leaving traces in every conceivable media and medium that is somewhat connected to her fields of work, from labs to galleries, from Lancet to Wired. She allows bacteria to work on marble, she lets music communicate with plague, and for what it's worth, she opens up the door for artists who want to test their BioArt pieces for ethical aspects.

The serious subjects of her research are not only substantial to the entire existence of humanity, but also question the nature and goal of art. As a scientist, she addresses these questions to the audience, as an artist expecting it to respond with sincere reaction, whether it’s fear, excitement or disgust. What ideas are behind her mesmerizing projects? What philosophical concept drives the daily routine of this grand artistic figure? We sorted it out in a conversation with Anna Dumitriu.

© Anna Dumitriu, Susceptible

Interview

by Sima Piterskaia

You created a ‘Trust me I’m an Artist’ Toolkit, so that anyone who wants to create an event for investigating the ethical issues of their bio-art piece could do that. May it be used not only with art and scientific collaboration, but within art itself?

I think the toolkit itself probably needs a little bit of rewriting now, because times have changed, and attitudes have somewhat changed in the last 10 years too. It was originally meant to be a practical idea. Because artists were being prevented from making the art that they wanted and needed to make. And there’s a gap of understanding between the scientists who are judging what's ethically allowable, but quite often, it's not pure ethics. It's something else, reputation and appearance, and on the other side, the artists who don't really understand how that system works. So, they play the art game, they're witty and playful, and that method doesn't work, necessarily. I mean, it can work as an interesting approach, but it doesn't work to help you get the work made. So, it depends on what your goal is, in that sort of situation.

But nowadays, an institution might want to do a focus group, where they criticize every aspect of the artwork in advance in order to protect themselves from, for example, putting something on social media that might be problematic. That's part of ethics, as well.

It's this balancing thing, ethics is basically the situation where there are two opposing views and no clear way forward.

So the toolkit I made was for artists to help them get their work made in scientific settings. I don't know if it's a practical method for doing other kinds of self evaluation. If you're worried about things like that, then probably you might want to reflect on your approach anyway. If you're worried about, you know, falling foul of social media, then maybe you want to reflect on your approach.

But it is not only about social media, sometimes artists just do cruel things, like for instance Andrey Tarkovsky, who had a horse killed for his ‘Andrew Rublev’ film.

Technically, in the UK from where I am speaking, at least nowadays, that would be illegal. That would be animal cruelty. So you don't need ethics, when it's just a matter of law, the law is already there. If you violate the law, you need a different approach, and for that you need a lawyer. But, you know, in the situation where Tarkovsky was at that time, maybe that was a thing that happened quite commonly. So maybe there was a different attitude. Ethical approaches change over time, what seems normal in one era or culture can seem very wrong in another. Actually that idea of ethics being culturally specific was something I looked at in the book “Trust me, I’m an Artist”.

Back in those days, a general opinion of such cases could be different, but today things like that take place. For instance, in a case of a recent ‘DAU’ multi-series film, that is fiction, but basically a reality where actors (including non-professionals) spent 10 years in the 1930s decorations and had to obey the laws of that cruel Soviet era. During the process of filming, one of the actresses was sexually abused, which became a part of the movie, so there were some serious ethical questions addressed to the Berlin Festival committee about including that piece in the event. Might your Toolkit, or a part of it, be applied to a situation like that to prevent it from happening?

It's not where the toolkit was intended to be applied. The reason we, including my collaborators, did it like that was to understand the ethics committees in the various countries. Because one of the points made in the book is that it's literally different everywhere you go, and the ethics committee's approach is very culturally affected, I think. The British one just procrastinated for two hours and then decided that they probably didn't have the right to judge the art anyway. The French committee decided that we would need to go to a different type of ethics committee, and then the Dutch one was really down to earth. And they were like, ‘This isn't allowed’, ‘this is something that would happen to you normally’, ‘this is something that could happen on a Friday night in Amsterdam, and we're not controlling whether it happens there’. Then we kind of broadened it out and brought curators and other arts organizations into it, but that got a bit more complicated, actually.

So you could apply it for things like that, but it's like, you've got to get the Ethics Committee. You could take that person's work, either with or without them and present it to the ethics committee, and have them deliberate over it, but you need to pick the relevant ethicist. In this case that you’ve described you would need a sort of filmmaker who worked in that area, and you’d need an employment lawyer.

Where's this line between self censorship and unethical approach?

© Courtesy of Anna Dumitriu

You have to understand that how the artwork story is communicated to the public could be problematic. There's a study, for instance, that showed that the more people knew about vaccines, the less willing they were to have vaccines. I'm talking about a lay person that's been through a workshop on how vaccines work. And so, by the communicating nature of vaccines and how they worked, people can have the risk of less vaccine take-up. Leaving them more at risk.

In terms of understanding of how cell biology works, or even how cancer research works, and these cell lines that they use, is important. For instance, there's the famous HeLa cell line, which you've probably heard of, that was taken without consent from a black woman in the 1950s (her name was Henrietta Lacks, — note by LM). But it depends on what angle you want to take on things in terms of communicating to lay people because sometimes people don't hear the whole story and they misunderstand. I'm probably trying to say that by working with science, you realize how careful you have to be to communicate some of these issues and how sensitive you have to be.

I work with plague. In Europe, it's pretty uncommon these days. We know the horrible stories of the past, but it's pretty uncommon. There's some outbreaks in some places, there's even outbreaks in America, occasionally. But, you know, none of these people are averse to making a zombie movie about Black Death. Because It’s very unlikely to meet people who have the plague nowadays. It's possible, but it's unlikely.

Whereas if I'm working with tuberculosis, I meet people quite often who've had tuberculosis. And they really do appreciate the work because it gives them a way into understanding the disease and talking about it. But when you make artwork about tuberculosis, or diseases that people that see them are going to be experiencing, you have to be careful how you tell it, because you could really scare someone unnecessarily. If you tell the story without telling the balancing part. TB is treatable. Even plague is treatable if you catch it early. But you have to be careful to tell the story. Otherwise, it just becomes a sort of more sensational for the audience.

There are a few of your artworks that are tuberculosis-themed, such as ‘Romantic Disease’ dress, or ‘Susceptible’. Is there something personal about TB?

No, not really. I haven't had it or anything like that. But there’s a story on how I came into working with TB and bacteria. Back in the 1990s when it first became accessible to search the world wide web for useful information (this predates Google). I realized that the stories the general public (including me) were being told in the media were completely different to the things that scientists knew. Everything was just completely different, and now I think this distrust of science comes because it's all half stories.The newspapers don't tell you all the information. Or if they do, but they put it in the last paragraph, or ‘this story continues to column 10, page 10‘, and you have to look there to find the actual scientific facts.

In those days, the whole British public thought that E. coli was basically food poisoning. But then I found out by doing this reading that actually it's an integral part of our gut (I'm gonna say microbiome, but that word wasn't in common use then), of our immune system, and it lives in our gut, and it helps us digest our food. Yes, several strains can cause food poisoning. But if it wasn't the E. coli bacteria living in our guts, we wouldn't even be able to digest our dinners! Nobody ever tells you that! They tell you about the bad things, so there's this whole opposite story.

And I was like, that's amazing. And then I started to find out about tuberculosis, and collaborate with scientists who were working with certain high-profile bugs, and I met one that was a TB expert and began the collaboration. My mind was blown.

The idea that TB actually kind of influenced architecture — Modernism is quite related to TB. You know, the idea of the big windows where the light can reach everything, and these staircases with the gaps at the side, so that it wouldn’t collect dust.

The whole thing from that relationship of the Romantic poets' fashion, — even this idea of being very pale-skinned, is to look almost tubercular, almost like a consumptive.

And it comes to Lord Byron. The poet said: “How pale I look! — I should like, I think, to die of consumption … because then the women would all say, ‘see that poor Byron — how interesting he looks in dying!” When I was a kid, my mum used to look at me and say ‘She's looking pale and interesting’, because my skin was very pale. So all this intermingling of things — how the bacteria has changed our life, how they change the planet… We wouldn't be here if it wasn't for bacteria, changing the atmosphere. The government and public health all come from the Black Death from the year of 1346.

So nowadays we also use some very serious technologies, such as AI, for everyday goals or just for fun. For instance, AI technology is being used to create new avatars for our social media.

I actually did some this morning. I was playing with Lensa.

Did you enjoy the result?

They were fairly terrible. (Laughs). But there were some hilarious ones. There were only very few that actually looked like me. (Shows ones that portray her as a warrior, then a witch, then an angel. We laugh). I have a very weird eye and a funny round face, and that cost me £3.99!

This or similar AI technology is something that is used by special forces to improve face detection cameras that will be of a good service for the military. How do you feel about it?

I mean, they've been using it in the military forever, and genetic algorithms (GA). So the space shuttle had an aerial that was designed by a neural net. And they didn't look like a sort of normal standard designer human would make in that. There's a bit in ‘Ghostbusters’, where they said ‘Symmetrical book stacking. [...] No human being would stack books like this.’ I actually studied GA evolved neural networks at the University of Sussex when I was Artist in Residence in the Centre of Computational Neuroscience and Robotics (from 2004-2010) and I continue to hold a visiting research fellowship in Computer Science at The University of Hertfordshire.

I mean, that's sort of the goal of AI, to design things that you couldn't possibly design so they would work in every context, isn't it? I think you can't stop the people from using AI and face detection in the military, as they probably funded most of the research!

Doesn't it scare you, the ambiguous nature of that?

Yes. It might go horribly wrong. Absolutely, but a lot of the stuff that the military does goes horribly wrong. If not, most everything that it does goes horribly wrong. So I don't know whether using an AI will make it any worse. When I grew up, a teenage movie was ‘WarGames’ (a John Badham’s film about a young genius who starts World War III by hacking a military computer, n.by LM). So we already lived thinking like that a lot. It's not ideal, but then no weapons development is ever good. But it is possible to use it for good things as well. You can't say that any technology is inherently good or evil. It's just a technology. It's how you use it that matters.

Also, such technologies use real artists' pieces, to produce new ones. At least some of the artists claimed that their art was used in AI-generated images without their permission, and it went viral throughout the digital illustration community.

Oh, all this stuff is kind of a mess. That's why it's easier if your works are not purely digital or not the whole thing online. It's the nature of having stuff on the internet that it can be ripped off and remixed. So you need to license it properly, and all this sort of stuff. And that's why when you go to museums you can't take any photos of anything, because they've got lawyers who will deal with that.

But we artists don't have any hope of being able to afford those lawyers. Unless there are enough artists being affected that somebody wants to do a class action or something, then you'll probably get $3 or something at the end of it. There's not much we can do to fight it. It's a tricky thing.

Why do you think humankind enjoys things that could be harmful or unethical? Pop culture is filled with such things. Any type of violence and harm.

I think a lot of it all goes back to Aristotle and his concept of catharsis, that you can experience something vicariously through drama, tragedy, and humour. So you live through the person, if you're watching a soap opera, you're experiencing what they're experiencing in a secondhand, not dangerous way. So you're learning how those emotions work, and I think that's part of what people enjoy about watching things like that. There's a sort of mirroring between the viewer's mind, and how they respond to the actor that there's a connection from the actor to the audience. And I think in terms of things like bacteria, it's all to do with aesthetic theory.

So there's various sorts of aesthetic sensations that we're getting from it, and one of them's disgust, or the grotesque. There's a pleasure in the grotesque. People enjoy seeing monsters and things like that, but in terms of bacteria, you've got this sort of idea of the sublime as well, when “all the motions of this of the senses are suspended with some degree of terror” (Edmund Burke, Anglo-Irish philosopher of XVIII century — n. by LM). And so it's a bit like freezing in terror in front of something that can kill you. Or has changed the world.

For instance, in ‘A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful’ Burke talks about how the very littlest things can be sublime, and that purity of not being able to see something properly is sublime. So, Kant went on to talk about how there's this sort of mathematical sublime, where it's like the numbers of something that you can't hold in your head.

The bacteria-like infectious disease fits with the idea of the sublime that's sort of inherent in violence or something like that.

This sort of moment when someone shoots you and your brain cannot cope with it, there's something that your brain gives up on. It's almost pleasurable, because it's not so much firsthand, although sometimes it's sort of close to festering. A kind of pleasurable sensation you get from approaching terror, but stopping before terror. It's like trying out terror, but not going the whole way. It's what we get from a roller coaster ride, or if you see a huge tidal wave or a flooded land.

If you're caught up in a flood, then that's terror, but if you just come to a peaceful location that happens to have flooded or that the streets have flooded, that was what set Burke off. What set him off was seeing Dublin flooded, and he realized he had this interesting sensation. And he put it down to being this idea of the sublime. I think it's something to do with that sensation that makes it so powerful.

Are you trying to create this sensation of sublime and suspense with your artwork?

© annadumitriu.co.uk, Zenexton

I would definitely say yes. I try to give people an experience of the sublime if I can, I tried to bring quite a lot of beauty into it as well. There's that to lure you in, and then follow up with a sublime when you work out what it is you are looking at... Have you seen my ‘Zenexton’?

The one that is heart shaped. Yes. I loved it. And the story behind it, that it kind of recreates the alchemist Paracelsus’s amulet, intended to secure the owner from all diseases, including plague. Very interesting!

Although it looks a bit like a heart, it is the body of a toad, the shoulders of the toad. But I quite like the idea that it looks sort of a bit heart shaped as well.

And it mimics a toad’s skin, the texture of it.

Yes and on one side it's got a full moon there and some sapphires. And there’s the plague vaccine inside.

So how do people feel about that? Do they share their emotions when they have this interaction with your piece?

It's more like people's expression. (Laughs) One of my collaborators said that she would follow people around the gallery looking at the piece. Because she worked there and was one of the collaborators on the show. She said she liked to go to the show, hang around and watch people go round the piece. And they looked a bit confused, sort of stared at it, peered at it a bit. And then they looked at the label, — I try to do labels that get a little bit complicated sometimes — then they're like ‘Oh, oh!’

In your regular life, are you looking for this sensation? For example, do you watch scary movies?

I do! All the time. Okay, so you know, some of my my favorite horror movies are the ‘Conjuring’ series (paranormal activity films inspired by the lives of Ed and Lorraine Warren, the paranormal investigators, — n.by LM).

Are there any principles of your art that are applicable in your everyday life?

Well, I am very big on infection control.

So you sterilize everything?

No, I'm not obsessed. I'm just sensible, and I get very annoyed about the security theater. There’s an example, certain restaurants in a certain country make you wear a mask to walk into the restaurant to go to your table, and then you still sit in an enormous crowded room where nobody wears a mask. But you have to walk from 10 feet in and to do that. It's ridiculous. Why?

Other than that, I think this might sound boring, but I basically work all the time. You know, the thing I do for fun is probably go out to art exhibitions.

Looking at some of your pieces, such as ‘Fermenting Futures’, dedicated to the life of yeast or “ArchaeaBot: A Post Climate Change, Post Singularity Life-form”, it is easy to fantasize that one of your art’s target audiences is not only humans, but rather a bacteria which would eventually outlive us. Is that a fair guess?

It might be by luck. But Christian Bök, who's a poet, he has been creating a poem that can be written by Deinococcus radiodurans, which is a bacterium that can withstand radiation, and theoretically spaceships, and stuff like travel through space, and live past a nuclear holocaust or something like that. So he's trying to make some art that will live on in the future. But I don't know, I can't say that about mine. It's mainly targeted at humans. Also, it's very difficult to get funding from Arts Council England to fund work that doesn't engage human audiences.

Can any bacteria appreciate art?

I don't think they necessarily could. Aesthetics for a bacterium is probably something like a particularly nice sugar it can feed off, but we don't know what it's like to be a bacterium. How does it feel to be a bacterium? Does it even feel if it doesn't have a nervous system? But it does react to inputs and outputs, but it is very basic in that aspect.

I mean, they have a lot of very complex behaviors. I had an argument with a scientist once who criticized my use of the word ‘like’ when I said that the ‘bacteria like this'. She was like, ‘Bacteria can't like’. And later on in the same discussion, she used the word ‘stress’: she said ‘The bacteria was stressed’. And I was like, ‘How can they not like things but they can be stressed?!’.

I have thought about that because I've got this piece called ‘Unruly Objects’. I've been working with the University of West Attica, and they've been looking at the microbiomes of antiquities. I was quite interested in what artwork can you make that the bacteria would like. What would be a very pleasing substrate for them? I'm still thinking about that. I did paint a sculpture with Winogradsky Column mud. I thought they were quite liking it. Also, apparently, plants are very bad for antiquities because they can grow into them and make holes and things. And then the bacteria get in as well, and that all breaks it down. I want to make it into a big artwork one day. A huge outdoor public artwork.

When I was reading about ‘Unruly Objects’, I was looking for a place where a bacteria starts to actually communicate in a very human way, but it never happened. Unfortunately.

They can communicate using hormones and chemicals. They do this thing called 'chemical signaling', quorum sensing — that's another term for it. They express hormones, and they can communicate various things with each other. It’s quite hard for us to decode what they're communicating about, but they definitely do it. They use it to decide to spore or turn on virulence factors. If you get a certain bacterium in your body, and they just sort of hang around in there. They don't make you ill or anything until they get the sufficient numbers, which is a quorum, — they'd call it sufficient numbers. At that point, they would do something like turn on virulence factors, turn on toxin production. For instance, in Vibrio cholerae it turns on this toxin production, where it gives people ‘rice water diarrhea’, which is, you know, the horrible symptom of cholera. And they do this through quorum sensing. So there's a theory that if you could decode the quorum sensing and send signals back to them, you could make them behave in different ways. There is a possibility of that.

In one of your interviews, you were hoping that from that pandemic of COVID-19 experience we would learn something useful. It’s been three years since the pandemic started — have we actually learned something as humanity? What is the lesson?

How to do mass PCR testing and genomics at a massive scale. There's been quite a lot of little things learned I guess, like, what happens if the planes don’t fly for a while? What happens to the environment and things like that? Or what happens if there's no traffic? What happens to people's mental health? That's definitely a tough one because obviously, people need people. So being isolated really demonstrates that, and we've learned quite a lot about how not to do things.

That's quite a lesson.

I mean, we've learned a lot about how a virus like this spreads as well. Not just in the basic sense, but genomically, because never has there ever been such a genomic profile of a bug that spread through the whole world; and also in the fact that they sequenced the genome within a month, and we're able to plug that into vaccines so quickly. It's been very quick that we sort of got back to normal. Depending on where you are in the world — obviously, it's not distributed evenly.

I was just in Sweden last week, because I had an exhibition there. And I was talking to them because obviously, over here in the UK, we had this very strict lockdown. They didn't have any really strict lockdowns. We get told in the UK, that the way Sweden did it, was right, and we did it all wrong. And so it was really interesting to hear the people in Sweden go, 'Ooh, we thought that you did it right in the UK. And we did it all wrong.' It really depends on from where you are — so it's perspectives as well, isn't that? We're still in the process of finding things out. We’re definitely learning, I think. Everyone was just doing their best in a difficult situation, but we have the data to really understand what was best. If we can look at it objectively.

And then we're learning things on a personal level, I suppose. Now that a lot of people don't want to go back to work, and lots of people started their own businesses. Now, as they don't want to be employees, there's a labor shortage across the whole of Europe. So that's something people learned on a personal level. Maybe what they wanted to do more, rather than just going to work in the dark and coming home in the dark.

I think you always learn something. Even if it's ‘Don't do that again’.

About that. 2022 is a year of massive, ongoing, worldwide spread military conflicts. Didn’we learn something from the previous wars?

That's an interesting question because it's a sort of generational thing. We're far enough from World War II now, those people mostly died. And so that opinion, what it was like, was maybe forgotten. People don't realize how awful it is. So then it came around again, basically.

That's why I'm always interested in looking at the history of things. Because I think we forget so much. We do need to learn things, but we forget, like, there's so much information out there. And people connect through stories, they don't connect through data. You can tell someone how many people died in World War II, but again, they can't hold it in their brain. The horror of that. This is sort of sublime too, because we're removed from it. And even if you attempt to understand it, you can't hold it in your brain anyway. It's either it's so bad that you can't deal with it. So then you forget.

Were any of your working processes affected by the wars?

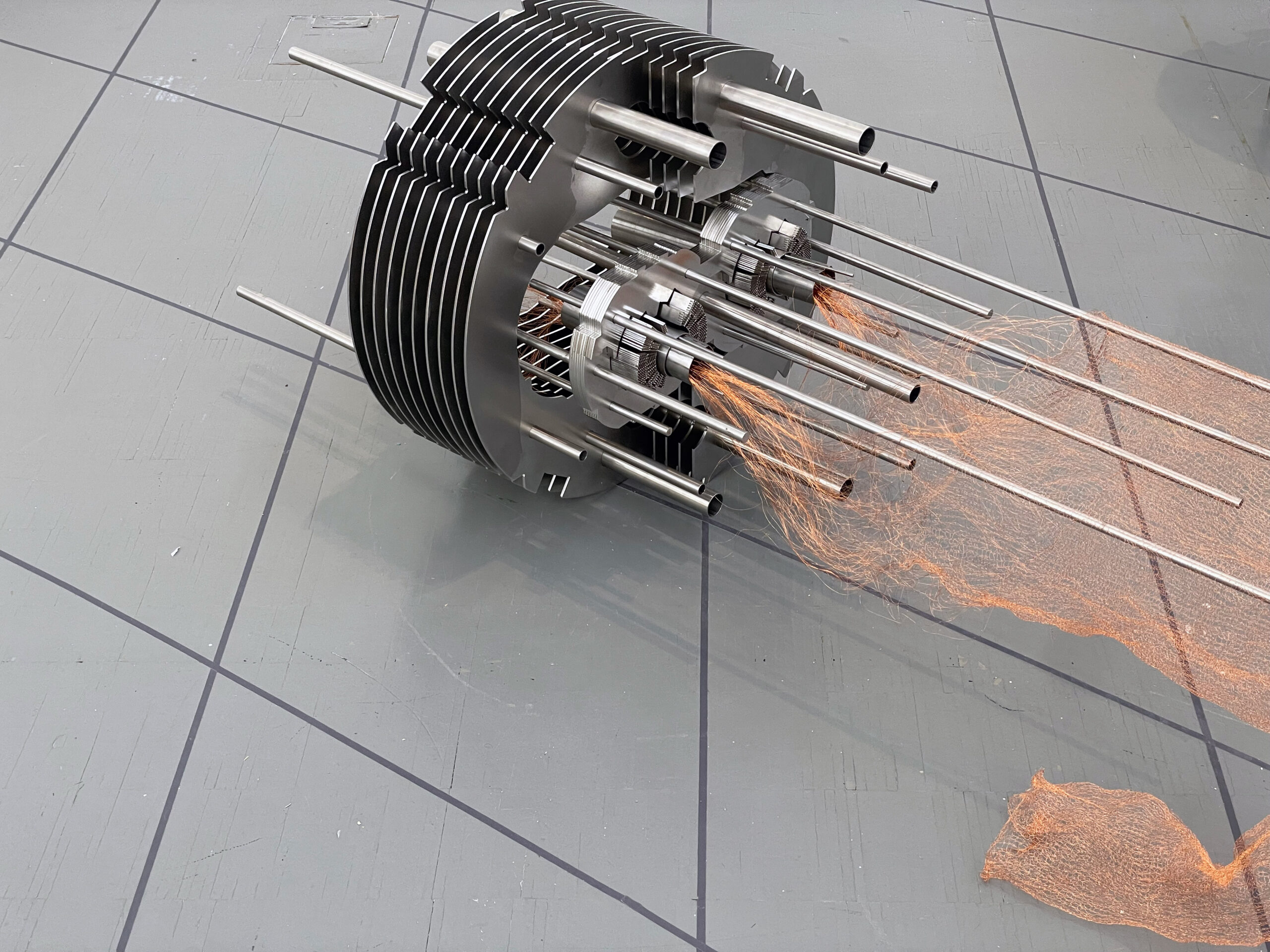

It's really trivial compared to the wars, but I do a lot of 3D printing of metal in some of my works. And that was quite delayed, because metal is for the war. Also the price of certain metals has really gone up ridiculously as they're being used for other things.

But other than that, more globally, were there probably some projects that you know about that were stopped or postponed because of it?

I feel sorry for some curators I know in Russia, because they are just curators working in art and science and they have nothing to do with the regime, but they can't collaborate internationally. So that's awful for them. I feel sad about that. Some very nice people. I don't like to see this sort of attitude where you can't work with people from one country or another country. The more you isolate people, the worse things are gonna get, because they might start to enact that isolation, rather than being more connected.

Have these later events in the last three years, such as Coronavirus, affected your perception of the concept of home?

Not that much. I still travel, I've been traveling a lot. When I got stuck here, I wasn't happy about that. I like to see new things, get new experiences, show the work, and meet people. And it's physical work: I want it to be in front of people, and them to be able to see and experience it. So I can't say I was particularly happy about the Coronavirus situation, from the nature of home things.

The only sort of positive-negative was — and this is a personal thing — that my dad had Alzheimers and he died in 2021. And if it hadn't been for Coronavirus, I'd have probably been traveling all the time. Because I was stuck here, I was able to be with him all the time. But I was able to go and visit and help look after him. So there was that kind of 'positive' side.

I'm sorry about your dad. My condolences. Back to the idea of home — what is your perfect place?

The place I do art. I do it either in my apartment in Brighton or in my studio in Brighton mainly, or in a laboratory. Last week I visited the Wellcome Sanger Institute, near Cambridge, in Hinxton. There I was working with scientists to extract the DNA and look under the microscope at syphilis bacteria: Treponema pallidum. It has been possible to culture it in vitro in the last two years. Before that, scientists in the USA were keeping the strain alive. It's a strain from a patient in 1912 that had neurosyphilis, which is the third stage known as tertiary syphilis, as they call it. And it's been kept alive in rabbits, in the testicles of male rabbits to be precise, for 110 years!

So we had some interesting conversations about the idea of people keeping this esoteric knowledge: these people in this lab, they're the guardians of these rabbits, and they keep adding new rabbits. But now they don't need live rabbits because they found a way to do it without and they're trying to develop other, better ways of doing it. And now they can study it properly because, until now, it was much harder to study.

Last week, I was working on that. That was really nice studying because the scientists have great conversations, and learn all these amazing things.

So your ‘perfect place’ is a place where everything is practical, and you can use that in order to create new pieces and do your research. Right?

And conversations with people about it. And then a big space that is all clean. And if I had some assistants, that would be nice cleaning up after me: I'll make a huge mess when I'm actually working on the making. Not in the lab, I'm perfectly tidy in the lab. But in the studio, whatever I'm working with explodes all over the place. Usually, whether it's textiles and threads and bits of cloth and/or paint, or marble dust. There's some sort of explosion happening around me!

Are you a passionate person? Do you create out of your emotion? Or maybe there's only an intellectual impulse?

Well, my father, because he was very English, used to say: ‘You're like an Italian!’ — because I was getting excited and waving my hands about when I talked. My Italian friends say that this is true. So I think yes, I'm fairly emotional and really passionate but I also have quite a cerebral side. Maybe it’s a good mix.

So you're more of an artist than a scientist, or it's vice versa?

That might be a misconception of what scientists and artists are like because they're not so different.

It takes passion to create something.

And to do science. Yeah, and obsessiveness. And the same with art. It's fiddly. It's time consuming. They're not that different.

Visit Anna Dumitriu's website.

Selected Articles

Two ChairsProject type