A dialogue on art, philosophy and self irony

March 20, 2023

The Voiceless Shout: The homelessness and Art

How artists reflect on homelessness and those without a home create art

© 'Denzel' by Richard Hutchins, richardhutchinstudio.com

Resource inequality and other global disasters of the modern world force many people to the point where they are alone, abandoned and deprived of basic rights and needs such as a roof above their head.

Many of these unfortunate souls are artists. How do they deal with homelessness? And how do fellow artists reflect upon that? We will talk about it in our article.

Words

by Boris Starodubtsev

We are living in times of Permacrisis (there really is such a word now), and no wonder that some humanitarian problems that seemed to be under control at some point, are getting worse. Homelessness is on the rise in New York, London, and other cities across Europe and the US. The problems with which the Global South had to deal with for a long time, finally descended on the Global North.

In case you've missed the last decade of battles, we'll help you catch up. It’s a chain reaction of juggernauts crashing all in their path where the capitalistic structure of the world leads to overproduction, which leads to climate change, climate change leads to natural disasters, which leads to people losing their homes. At the same time we have the political instability and the military conflicts in many regions, including, of course, Europe, and that leads to the massive migration and people fleeing their countries. And the migration politics is far from perfect in many of the First World countries (it’s sad how the Cold War conception hasn’t yet lost its accuracy), which is focused on the production and sales, not on the well-being of the people in need. And here we are on the first link of the chain.

The world of art is affected by these shocks in many different ways. Some artists choose it as a theme to work on and bring attention to, some artists actually become homeless, because not all the art in the world is in demand, and some homeless people try to find a new home and new sense in it all and turn to art.

Lunatum will cover some of these cases in this article.

Signs of Homelessness: Exploitation or Activism?

Willie Baronet, an American design entrepreneur, has been buying signs of homeless people since 1993. First he didn’t know why he was doing it, but later this process transformed into a series of art projects. In 2014, Baronet and three of his collaborators made a film called ‘Signs of Humanity’, in which they traveled through the US buying signs from homeless people and speaking to them.

Having made homelessness a center of his research, Baronet not only raised awareness about this state of being, but also tried to find an answer to the question: what is home?

‘Is it where you sleep? Is it where you are from? Is it a house or an apartment?’ he asked at a TEDx event. He recalled his childhood experience in which he was the oldest of eight kids, his father didn’t make enough money and had anger management problems. For Baronet, home was a scary place, where he didn’t feel safe and had to sleep with a pillow over his head so as not to hear what was happening in the next room.

Baronet is not the only one who used the signs made by homeless people as art. In 2013 Andres Serrano, a photographer whom I have known since childhood because his photos were used for two of Metallica’s album covers, bought about 200 signs from the homeless people of New York. He called it ‘Signs of the Times’, and his goal was almost the same as Baronet’s – to let the voices of the homeless be heard, especially by those who prefer not to notice them at all.

Serrano wrote in detail about his experience. The youngest person he bought a sign from was a 16 year old girl. Her sign read ‘Mom told us to wait right here. That was ten years ago’. The others contained different messages, some of them were sad – ‘Need a miracle’, some pretty harsh – ‘What if it was you?’, while others were hilarious – ‘Obama doesn’t accept change,but I do’, and all of them told a story.

Serrano created several projects about homelessness in his native city. The first goes back to 1990, one of the latest was held in 2014. It was called ‘Residents of New York’ and consisted of the large-format portraits of 85 men and women living on the NY streets. He tried to engage the locals by hanging the photos in the subway so that any citizen could see them on their way to work or home.

“Hopefully next time you see a homeless person you actually see that person and maybe you think, oh yeah, let me give them some money,” he said in the interview.

So what was it? Is that project by Serrano really a project about art or is it more of an activist gesture? Did he follow the ‘nothing about us without us’ rule, which is applicable to any marginalized or discriminated group? And did this activity actually help someone but the curators of the exhibitions and himself? Is it necessary for an artist to experience the problem themselves or is it enough just to feel empathy and to attract attention to the problem? We don’t know for sure, but that’s probably what artists should think about while working on socially oriented projects.

Painting hope and fear – or colonialism?

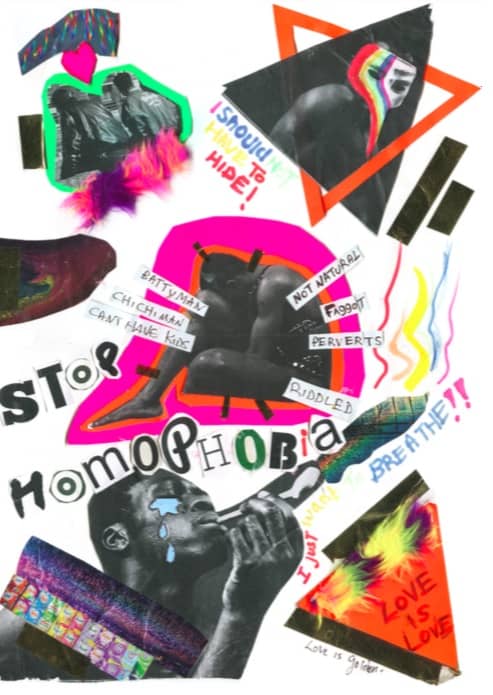

© James Earley, "Matthew", jamesearleyartist.com

James Earley, a British hyperrealism painter, has been painting homeless people since 2015. In his article, he wrote: “I have been asked by galleries to paint other subjects – ‘anything but the homeless.’ I have been told that nobody wants a painting of a homeless person on their wall.”

He was told that painting other subjects would bring him more money, and still his heart was with the homeless. It was them whom he wanted to paint. He painted them on the streets of England, Spain, France, Holland, and the US. Like Baronet and Serrano, he tried to get to know people who agreed to be the subjects of his works.

Earley singled out one of his heroes named Joe Crow for his ability not to look down in spite of all the problems and traumas he dealt with. By painting him, Earley tried to paint hope and fear on the same face. He managed to do it by changing the lighting and dividing the face in two.

He also described a most distressing situation he experienced in the French city of Toulouse. Most homeless people yearned for a conversation, a dialogue, but there he met a man with no hope in his eyes. There was no movement, no reaction. The mere despair and hopelessness as they are. Serrano described a couple of similar people who said “no” to any attempts to communicate, just wanting the world to leave them alone.

That probably means that a higher percentage of homeless people actually have some hope, some fulcrum not to slow down to no pace at all. Anyway, like always, those who need help the most don’t eventually get it.

Earley created undoubtedly amazing art, and his hyperrealistic works are very impressive. But is there more awareness or actually exploitation? Does he use it to his advantage like Da Vinci who made sketches of homeless people fascinated by the deformities of the human body? Is his motivation similar to Gogen’s who painted Tahitian women? It’s not like there are definite answers to these questions, but sometimes we don’t notice our own “isms”, and that’s why they must be asked.

In any event, the ones who tell the most relevant stories about homelessness are not the ones who turn homeless people into a project, but the artists who don’t have a roof above their head themselves.

Let’s hear their voices.

Welcome to the Festival of Homeless Arts

In January, the One Festival of Homeless Arts event took place in London. The festival is held to exhibit art in different forms made by artists who are currently or used to be homeless.

It is not the first time for the event. It was founded in 2016 and was held until 2019, and then the pandemic loomed over the world. In October 2019, the BBC interviewed some of the artists from this festival.

One of them is Geraldine Crimmins. The whole story of catastrophic deterioration, like it often happens in the aftermath, is told as the plain facts of the biography. Geraldine shared her story about two businesses she used to have, and how her mental health began to get worse in her late 30s, and how she lost her businesses and also a house and became addicted to drugs and homeless in her 40s and how she was sent to prison at 50. Geraldine said that prison saved her life because she detoxed there. She also attended an art class while in prison. Now she positions herself as an artist, she is also a mentor for people with mental health issues.

She describes her art as simply as she describes the personal disasters crashing her life in the past: “I’ve always liked the female nude.” That’s just what she began to passionately paint.

She lives with PTSD and anxiety disorder now, and that’s one more layer that can be out of attention: homeless people don’t have access not only to the warm room with a roof without holes, but also to the right medication and psychological help. Living through a destroyed life requires a lot of mental energy, and sometimes the only source of this energy is not having your life destroyed.

© Geraldine Crimmins, IG

Geraldine seems to be doing just fine now. She is active on Instagram, and actually that’s how I discovered that the One Festival of Homeless Arts would be held once again.

There are two more homeless artists with whom the BBC spoke to. One of them, Stephen O'Grady, looks like a pretty happy man in the photos. “Move to Seaside when you are homeless” is pretty good advice from him, a little bit romantic even. You look at him going everywhere with his sketchbook and almost think there is nothing wrong with his situation.

Another one, Claire Bastow, experienced homelessness several times, first back in the 80s. When she was a child, she went to art galleries with her grandfather Basil Bastow, a watercolor artist. Claire herself mastered her skills in her late 30s. She focuses on large scale portraits, and often her subjects are homeless women.

More than three years have passed since that interview. Geraldine Crimmins is still active. There are no updates on Stephen and Claire.

As for this year's festival, as I am writing this it is happening. It doesn’t have too much press coverage, but it has a good Twitter, and it seems to be a good platform for people for whom art is a home.

That’s (Home Is Where the Art Is) actually the name of the film about David Tovey, an artist that used-to-be homeless who organized this festival in 2016.

His life was pretty normal, even successful, and he owned his own pub. Then he was diagnosed with neurosyphilis, cancer and HIV. While in the hospital, he began to study art. At the same time, he couldn’t pay his rent anymore and lost his home.

In the abovementioned film, he gives some tips about manageable homelessness. He shaved a lot, for example, and he found parks with fruits, he never begged for anything. He also found fresh food thrown out by some cafes. He recalls steaks and cakes with special reverence.

When he turned to art, his life changed for the better and he even had a fashion show at Tate Modern. What Tovey really emphasizes is that anyone one day may just become homeless. There are too many things that you can’t control at some point.

Story of Success?

When it comes to the poor, there is always a cinematic story among the hundreds of boring stories and thousands of failure stories. As typically as this can be, it is a story of an eccentric white person helping a person of color in need that is living in dire straits.

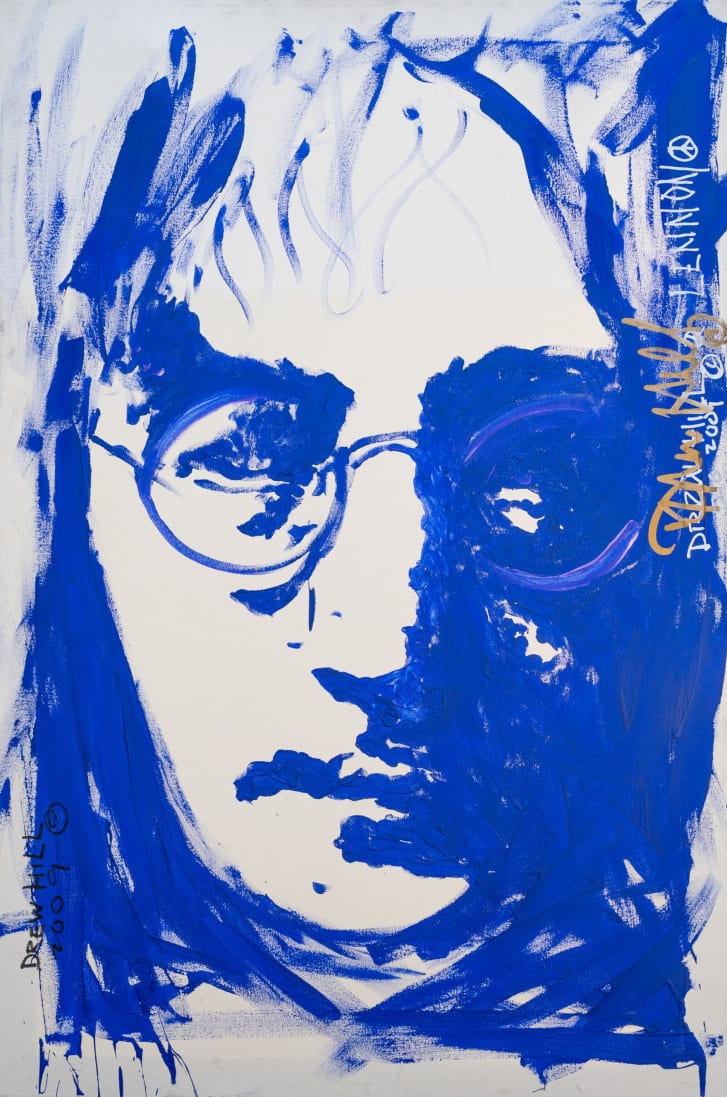

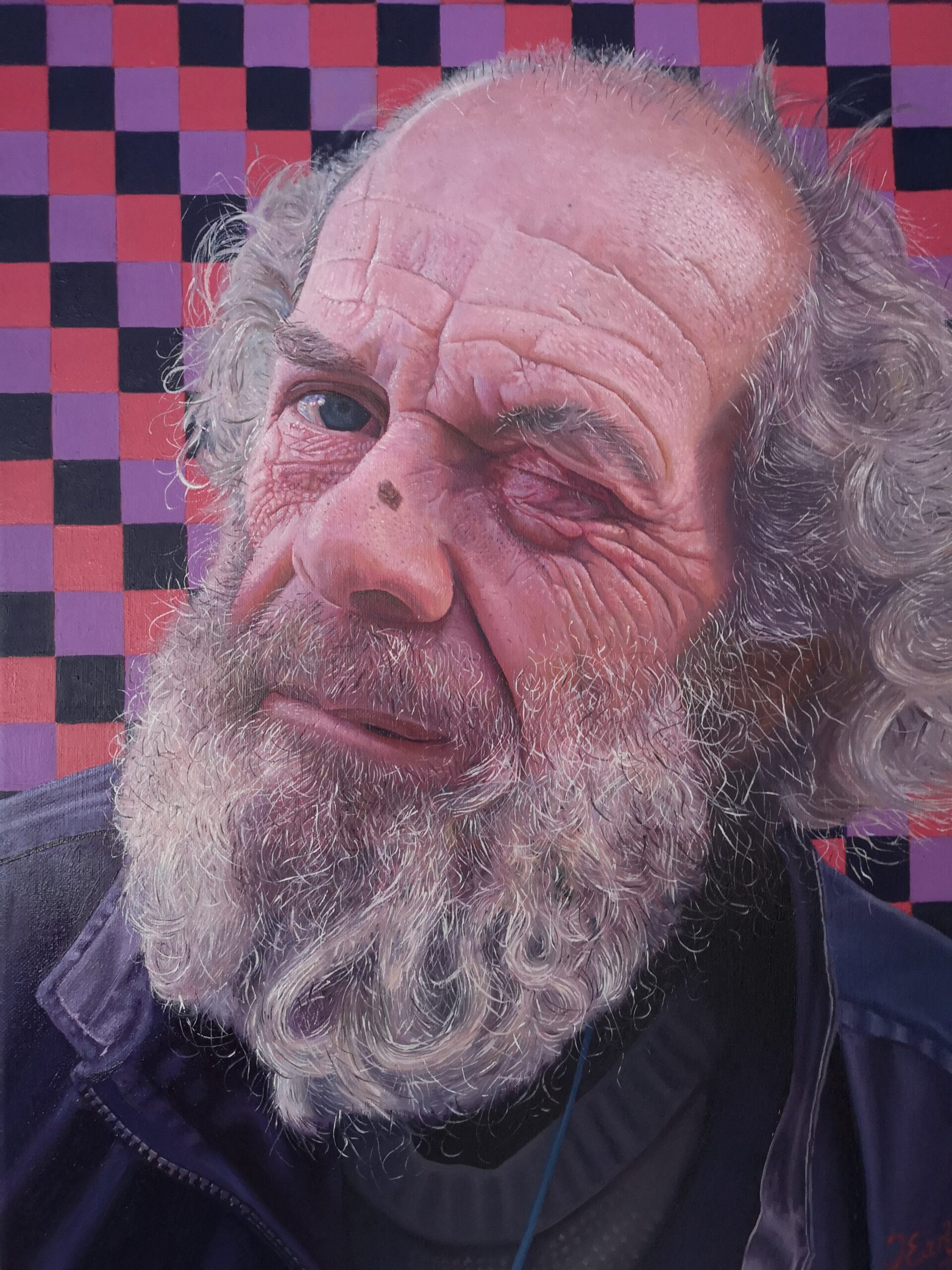

Richard Hutchins is an American artist in his 60s, who was homeless for six years till 2021, when he became an Internet sensation after he accidentally met a rich white guy who helped him.

Richard painted and drew since childhood, but at some point he was sent to prison on the accusation that later appeared to be false. While he was in prison he succeeded at making the envelopes which he used to send letters to his friends. He was an amazing envelope designer.

When we talk about art we sometimes forget how much the production of it actually costs. Everything is expensive: paper, canvases, pencils, paints and other accessories. And Hutchins reminded us of it, when in prison he tried to solve this problem.

© Richard Hutchins, "Blue Lennon", richardhutchinstudio.com

First, all he could use to draw with was a pencil, but then he got an idea to use some dye from M&M’s and Skittles. He also made a brush using hair from his beard. And then he tried to use everything he could get his hands on – from coffee to toothpaste.

After prison, he worked as a painter in a California studio, but a fire destroyed it and also about 800 of his works. Soon he became homeless and had nothing to paint with. Then by accident he met Charlie ‘Rocket’ Jabaley, who used to be a music producer, and then he was diagnosed with a brain tumor, and then he lost weight and became an athlete, reversed the brain tumor and decided to be a philanthropist.

Since that fate-changing meeting Jabaley has begun to curate Hutchins’ life and newly found career. He started with buying him some working tools and continued by promoting his art. Some famous people like Oprah Winfrey bought his painting.

There is still a lot of work on sale now on Hutchins’s site, including the originals. The original John Lennon painting is $23,000, and the original Lil Wayne painting $15,000. Originals of the envelopes go for up to $12,500, but the prints are cheaper at about $200 each.

The site says “help get Richard off the streets and into a home.” We can't tell for sure whether this is a catchy line or reality, considering the cost of living in the US.

Returning agency: A book of homelessness

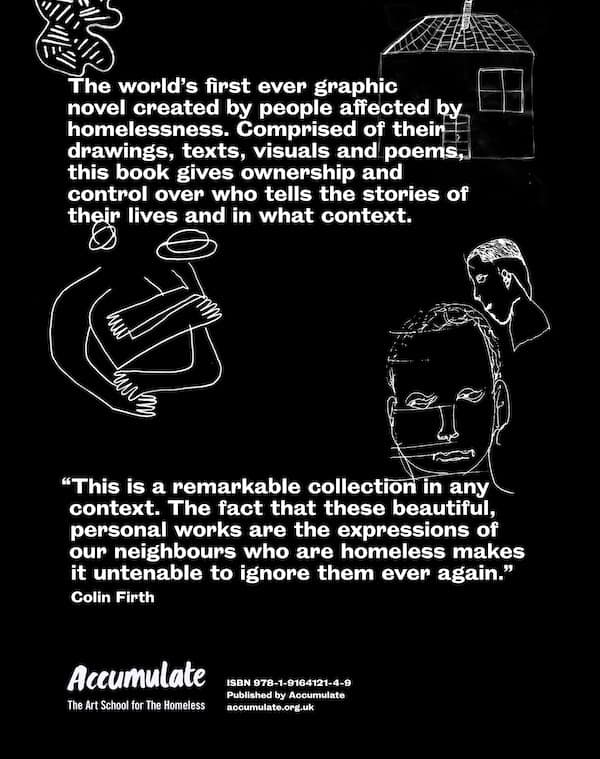

One more example from the UK. Since 2013, there has been the Accumulate Art school for Homeless – a charitable organization that provides different courses and workshops for homeless people such as knitting, drawing, teaching how to teach art, street art, filmmaking and even fashion. Their main focus group are young homeless people.

Through these creative initiatives, Accumulate tries to help people “take control over telling their own stories on their own terms.” Like some artists we mentioned above, this initiative aims at giving a voice to let the stories be told and heard. This one gives more than it takes since the homeless are the agents here, not objects, and are supported along the way and not once a year.

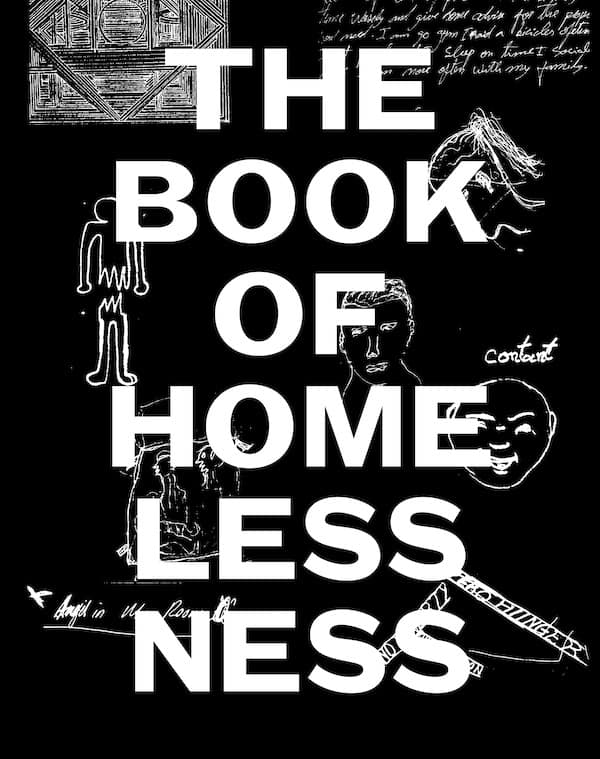

© A Book of Homelessness by the Accumulate; accumulate.org.uk

Accumulate was founded by a Marice Cumber, an artist, who makes awkwardly beautiful oversized ceramic cups (or maybe they are vases) with supportive and psychologically careful sayings like “I did the best I could”, “The playground is all mine”, and “I lost myself for a while.” The works are about resolving and rationalizing emotions and inner conflicts. She didn’t actually make ceramics for 30 years, but then returned to it at the age of 57.

Like many other funds, this one has a beautiful merchandise range, and a book of homelessness is on top of it. This is an anthology of stories, drawings and comics created by people affected by homelessness in one way or another.

In an interview for Dezeen, Cumber said that once you are excluded and marginalized from society, control is what you lose. You don’t have a choice any more, you can’t choose your food, your clothes. You can’t choose your way of life, and survival becomes the only goal. You don’t control anything.

She highlighted that people from this book became homeless after different events, but what they had in common is that they had to flee, to escape, to run from something much worse than homelessness.

It’s not an easy read, of course, but the book is a work of art for sure. On the Accumulate site it costs £25. Consider it a personal recommendation.

Map of the Problematique

By this short tour around the artists and homelessness topics, we are probably able to state that something is being done. The artists raise awareness about the homeless people and highlight the fact that their stories are worth listening to, and the homeless people have the framework to share their art and to actually acquire the skills to make it.

© James Early, "Antony's Answer" jamesearlyartist.com

The question is, how many of them and for how long? When Serrano was asked in the interview about the people in photos, whether there were some of them he met more than once, he said that between the Signs and Residents projects most of them ‘were gone’. He didn’t clarify what he meant, but he proved there is a connection to the project and there is no connection to the people. Unfortunately, since Serrano’s project, the homeless rate among younger people in New York City has been on the rise.

It is also difficult to differentiate the inner sense of the support some of the homeless artists get. How far is it from patronizing? Is everything fine when a random guy makes you famous and then is always around like a shadow?

In addition, it’s difficult to evaluate a work of art without being biased. Would the works of Geraldine Crimmins impress you if you didn’t know about her background? Would the photos of Serrano impress you if you didn’t know about the social vector?

Besides, there is always a meaningful question which we mentioned as the one raised by William Baronet. What is home really? Why are there so many situations when home is a more dangerous place than not home?

Finally, if we deepen the idea of David Tovey and take his experience into account, we’ll see that anyone can end up out there on the streets. The world is torn apart by wars, economic crises, political instability and thousands of personal issues that push too hard on a daily basis, and that means that such things in anyone’s life can happen all of a sudden. That means that there are no ‘us’ and ‘them’ when we talk about homelessness, and thus the art of homeless themes and homeless art is relevant to everyone.

However, let’s end on a high note. Projects like Accumulate really help to return agency to homeless artists, not just to raise awareness about their existence. And art is really a wonderful tool to get your story heard. You have your voice, your thoughts, your issues and your traumas, and there are people who would want to listen to you share it. Maybe that means that home is where you can tell your story without being judged or accused, and art is a good pathway.

Edited and idea by Sima Piterskaia

Selected Articles

Two ChairsProject type